Where did yoga start?

By now it’s fairly common knowledge among those who attend yoga classes regularly that Yoga has some connection to an ancient spiritual practice. However, it’s not always well understood what that connection is.

Where does Yoga come from? What does the ancient understanding of Yoga have to do with our modern yoga practice? Are they similar or different? How has it changed over the years?

It’s not just beginning yoga students that have trouble answering these questions. There has been much debate over the years among historians, anthropologists and practitioners of yoga as to its origins. Much of the potential source material has been lost to history, so we generally have to rely on the few texts and oral traditions that have survived, not all of which are directly relevant.

However, due to the renewed interest in Yoga throughout the world in recent years many scholars, in India and abroad, have begun to focus on such questions. Their work is illuminating but there is still much that remains unsettled.

The spiritual and mythological traditions of India help to fill in the blanks. Tradition informs the experience of it’s practitioners and creates the atmosphere in which it is taught, practiced and lived.

Here we will explore the History of Yoga drawing from both the modern historical understanding and the traditional one.

Let’s start from the beginning:

What is Yoga?

Yoga is derived from that Sanskrit root word “yuj” which means to join or unite. The simplest translation of the word yoga, then, is “Union.”

Which begs the question: “Union of what to what?”

The simplest answer is that the practices of Yoga are intended to unite the mundane, separate, material aspects of the self, with the divine, connected and ethereal aspects of the self. In many forms of Indian philosophy, the idea that they are not united in the first place is maya, or illusion.

There are many different methods of achieving yoga, each of which has its own schools and philosophies about how it is best accomplished. However, they are all, at their core, attempting to liberate the individual consciousness from Maya and in doing so, merge with the supreme consciousness. Or perhaps, to realize they were never separate in the first place.

When we think about yoga in this light, the answer as to when it originated is simple. The basic philosophical premise of yoga carries with it the implication that the possibility of liberation is a basic part of what it means to be human.

So, yoga has been around for as long as humans have. It’s an open and shut case.

But what about the practices of yoga? Well…that’s a much more complicated question.

The Indus Valley Civilization

The earliest archaeological sites in the Indian sub-continent are known as Harappa and Mohenjo Daro and are located in what is now modern Pakistan. They date back to around 2600 BCE and are thought to have been the major cities of a large empire known as the Indus Valley Civilization, which would have formed around 3300 BCE.

The Seal of Pashupata was found in the ruins of the Indus Valley and is thought to be the oldest representation of a yogic technique known to mankind.

The seal represents a seated figure with three faces generally regarded as the Hindu god Shiva. Shiva is depicted sitting in Mulabandhasana, a highly advanced seated posture with both the knees and toes on the ground and the heels lifted or turned forward so that they press into the perineum.

This pose was commonly combined with long periods of meditation and fasting in later yogic sects.

The Seal of Pashupata is one of the key sources of information on the religion of the Indus Valley Civilization and though there is much room for interpretation, it seems to show that some form of yoga existed that was similar to the yoga practiced in later periods.

The Vedas and The Upanishads

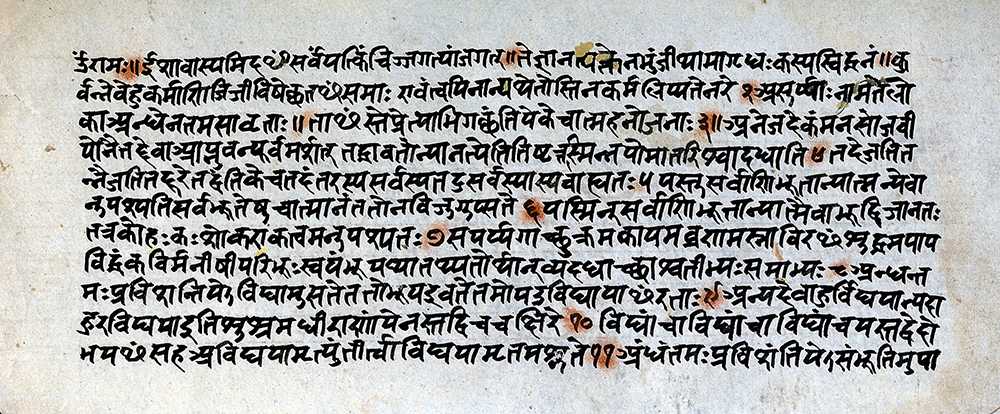

The Vedas are the earliest known written texts of the Indian religious tradition. They are a large body of scriptures that have been arranged in four separate volumes. The Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvaveda. They were most likely written during a long period of time spanning from 1500 to 500 BCE.

While most Vedic literature has no direct reference to any technique called Yoga, they were traditionally thought to have been composed by rishis, or sages while in states of deep meditation. The main portion of the Vedas are made up of mantras, hymns and directions on performing ritual and sacrifices, all of which, it can be argued, are themselves forms of Yoga

However, the most interesting part of the Vedas from a yogic perspective is a collection of close to 200 short texts called The Upanishads. They are philosophical texts that form the basis for all subsequent Hindu thought and had a strong influence on Buddhism and Jainism as well.

Traditionally, the Upanishads are known as Vedanta, the “end,’ or “highest point” of the Vedas. Today they are the only part of the Vedas that is commonly read outside of a ritual setting and they have become among the most important texts, not only in Indian intellectual history but in world history at large.

The Upanishads contain discussion about Yoga, mainly in the form of mantra and meditation, but they are significant primarily for providing the philosophical basis upon which yoga depends. Namely, that Atman, the soul or personal consciousness is either a part of or identical to Brahman, the supreme consciousness. As we discussed earlier, the union of Atman with Brahman is what the word yoga means.

The Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita is perhaps the most important scripture of the Hindu religion. It was composed around 200 BCE and makes up a very small portion of a much larger work called The Mahabharata, a great epic concerning the war between two rival groups of cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas.

The story of the Bhagavad Gita follows Arjuna, one of the Pandavas, as he drives his chariot into the centre of the field of Kurukshetra to observe the two armies amassing before a major battle. Torn between his duty as a warrior defending a righteous cause and the realities of going to war against his friends and family members, Arjuna is despondent.

He is accompanied by his friend and advisor Krishna, who also happens to be the eighth avatar of the god Vishnu. In other words, he has descended to earth and taken a human form. The Bhagavad Gita revolves around the conversation that Arjuna has with Krishna on this fateful day.

One of the things that is discussed is yoga.

Krishna lays out and discusses several paths that lead to union with the divine. The most important of these are Jnana Yoga, Bhakti Yoga and Karma Yoga.

The Three Yogas of the Gita

Jnana Yoga is the yoga of spiritual knowledge, wherein the practitioner achieves liberation through a process of study and self-inquiry. The practice of Jnana Yoga involves the contemplation of such fundamental questions as “Who am I?”, “What am I?” and “What is the nature of the self?” It is generally pursued with the aid of a spiritual teacher or guru.

Bhakti Yoga is the yoga of devotion. The practice of Bhakti Yoga involves prayer, the repetition of a mantra and the singing of religious songs, or bhajans. These practices are all intended to merge the practitioner with the divine through loving devotion to that divine force in the form of a personal god.

A Bhakti Yogi will usually direct their worship and prayers toward a statue, or murti, that depicts one of the Gods many embodied forms, such as Shiva, Krishna, Ganesha, Kali, Durga or Hanuman.

Karma Yoga is the yoga of unselfish action. It is often thought to involve charity and community involvement, and indeed it may. However, the main process of Karma Yoga is an internal one where a practitioner learns to do their work in the world, whatever that may be, without being attached to the fruits of the action. A sincere practitioner of Karma Yoga dedicates all their action to a higher purpose; serving God.

A key principle in the Bhagavad Gita is the concept of dharma, which could be translated as either duty, purpose or fate depending on the context. The idea is that a person is born into this world with a pre-ordained set of circumstances and pre-dispositions that will lead them on a certain path in life.

In the Bhagavad Gita there isn’t one yoga that is preferred above the others, nor are they mutually exclusive. Your dharma will determine which type of yoga is most appropriate for you.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

The philosophical traditions of Hinduism are generally divided up into six schools. They are: Nyaya, Mimamsa, Vaisheshika, Vedanta, Samkhya, and Yoga. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are the principle source text of the Yoga school of philosophy.

It’s important to note that the Yoga Sutras and the Yoga school of philosophy do not necessarily form the foundation of every school of Yoga. For example, many Jnana yogis would take the Upanishads and the Vedanta school as their philosophical basis. Many Bhakti Yogis would prefer the Bhagavad Gita.

However, when you take a teacher training course at a modern yoga school the text that is most often used as a reference is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and they are commonly studied by sincere practitioners of Hatha Yoga, particularly in the West.

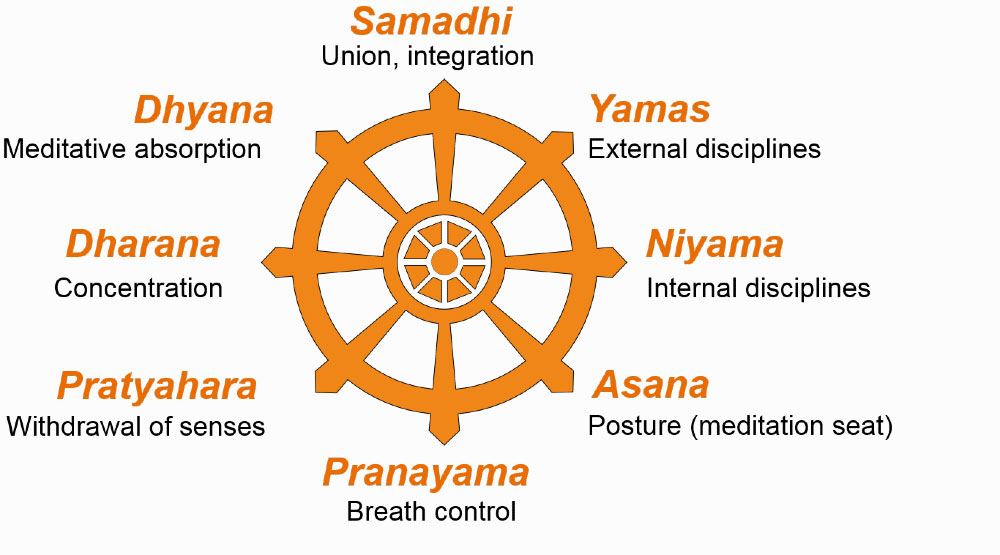

The Yoga Sutras are a collection of 196 incredibly dense aphorisms written down sometime before the year 400 CE. They concern the process of achieving Kaivalya, or spiritual liberation. This process is broken down into eight limbs. These eight limbs are the most important part of the work for the modern student of yoga.

8 Limbs of Yoga are:

1. Yamas – A set of five ethical precepts that govern one’s behavior towards others. They are:

- Ahimsa – Non-violence

- Satya – Honesty and truthfulness

- Asteya – Non-stealing

- Brahmacharya – In a monastic setting, this would certainly have meant celibacy, though for a lay practitioner it could also be interpreted as marital fidelity or sexual restraint.

- Aparigraha – Non-coveting, non-possessiveness

2. Niyama – Another five ethical precepts. These ones regard internal states and the relationship one has to oneself. They are:

- Sauca – Purity, cleanliness of mind and body.

- Santosha – Contentment, acceptance of circumstances.

- Tapas – Discipline and persistence, particularly towards one’s spiritual practice.

- Svadhyaya – Study and self-reflection.

- Isvarapranidhana – Contemplation of the divine.

3. Asana – Asana is what the postures of modern yoga are known as, though in this context it probably meant a simple seated meditation position that the practitioner can hold for long periods of time. The relevant passage states that your posture should be steady, yet relaxed.

4. Pranayama – Pranayama is the regulation of the breath. In Hatha Yoga, there are many breathing exercises that are referred to as Pranayama. However, in the Sutras the meaning is simpler. Pranayama is the slowing down of the breath in preparation for meditation. This can either include retention of the breath after inhalation or exhalation or the lengthening of the inhalations or exhalations themselves.

5. Pratyahara – Pratyahara is the withdrawal of the senses. This process is an internal one where the mind removes its awareness from the external world of objects. It does not literally mean the closing of the eyes or the stopping of the ears, though yogis would often meditate in isolated places like caves to help them achieve this effect.

6. Dharana – Dharana is the focusing of one’s attention on a single thing. It can be an internal thought-form, like an image or a mantra, or it could be a single point of sense-awareness, like the tip of one’s nose or the navel.

7. Dhyana – Dhyana is the state of meditation. After one has begun practicing Dharana, the process of achieving Dhyana can begin. Dhyana is a state where there is only a continuous stream of non-judgemental thought about the object, uninterrupted by other thoughts.

8. Samadhi – Samadhi is the final state of liberation, where the distinctions between the meditator, the object of meditation, and the act of meditating dissolve and merge with one another. In a state of Samadhi, there is only oneness.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika

In the thousand years that elapsed between the writing of the Yoga Sutras and the writing of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, there were many other texts expounding different methods of attaining spiritual liberation. Many of them would refine the ideas of the Upanishads and the Yoga Sutras into various systems and schools.

However, in all these texts you will find few references to the sort of Yoga that has become popular today. That is, a physical practice that involves the performance of postures and breathing exercises. The earliest work we have on a style of Yoga that resembles modern Yoga is the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika was written by the Rishi Swatmarama in the 15th century and it details a yoga that is highly concerned with the body. Firstly, it recommends a number of purification practices or shatkarmas, intended to cleanse the body of impurities and allow energy to flow freely. These include the practices of neti, nasal rinsing ; basti, enema and nauli, abdominal churning.

The work goes on to summarize the practice of a number of different asana, or postures. Many of them are seated, but some are physically challenging exercises that would be familiar to anyone well versed in modern yoga practice. Mayurasana, or the Peacock Pose, is an example of one such asana.

In addition to asana, the work also covers Pranayama extensively, in the form of breathing exercises. It also discusses energetic concepts like chakras, kundalini, and shakti.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika is one of a trio of works considered to be the canonical texts of Hatha Yoga. The other two are the Gherandha Samhita, which outlines a wider range of asana, and the Siva Samhita, which is notable for promoting the practices of yoga amongst lay people and not just monastics.

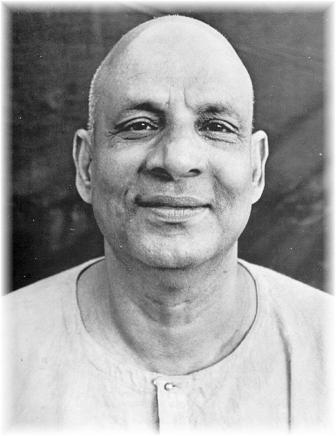

Swami Vivekananda

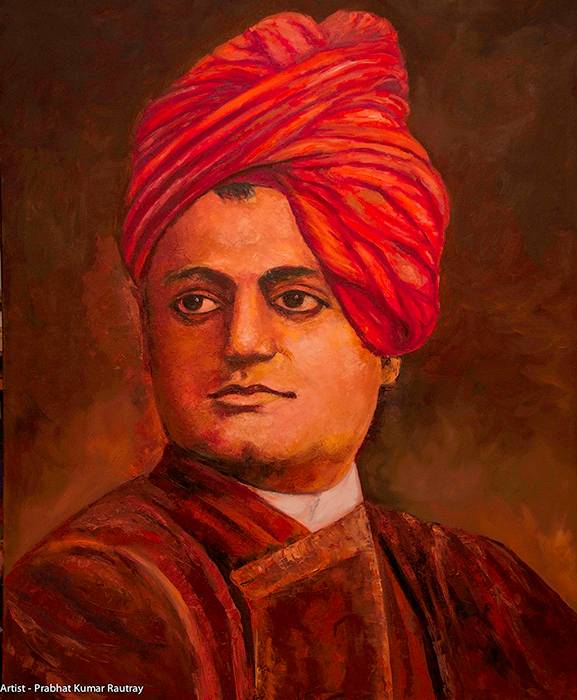

Swami Vivekananda was a Hindu monk who lived in the late 19th century and an ardent disciple of the beloved guru Sri Ramakrishna.

He traveled extensively in the west, living for a time in America and establishing the first Vedanta societies in San Francisco and New York. Through his popular public talks and writings, he was one of the first people to introduce the philosophies of both Yoga and Vedanta to the western world.

However, his influence was not merely felt in the west. He was one of the major voices in the revival of Hinduism in India, as well as the rise of nationalism in the face of British colonial rule.

By the 19th century, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali had fallen into near obscurity. In his text “Raja Yoga” Vivekananda single-handedly rejuvenated interest in the text and it subsequently became hugely popular with a western audience. It has been remarked that the publication of “Raja Yoga” in 1896 marks the beginning of modern yoga.

Many others would follow in his footsteps by traveling to the west, forming spiritual organizations and promoting interfaith dialogue. These would include Paramahansa Yogananda, who wrote the ever-popular book “Autobiography of a Yogi,” and founded the Self-Realization Fellowship, which continues teach his version of a technique called Kriya Yoga.

However, Vivekananda was the first, and he laid the groundwork at a time when religious tolerance wasn’t exactly commonplace.

T. Krishnamacharya

If you’re looking to point to the beginnings of modern studio yoga, you have to wait until the early 20th century and the work of a handful of pioneers. These include Yogendra, who founded The Yoga Institute in Mumbai in 1918, which is the oldest organized yoga center still in operation, and Swami Kuvalayananda, who founded the famous ashram Kaivalyadham which is also still in operation.

However, the most notable among these pioneers was Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. Krishnamacharya was a renowned scholar of Hindu philosophy who held degrees in all six schools of Hindu philosophy. In 1919 he traveled to Tibet and spent seven and a half years studying with a Himalayan yoga master named Ramamohan Brahmachari, with whom he studied asana, pranayama, and the Yoga Sutras.

In 1926 he was called to serve in the palace of the maharaja of Mysore. While there he developed a style of yoga that merged traditional asana with exercise principles borrowed from western gymnastics. It incorporated flowing movements linked to the breath which he called Vinyasa.

Some of Krishnamacharya’s students would go on to develop their own styles of Yoga based on different aspects of his teachings. They include:

- K. Pattabhi Jois, who would found the Ashtanga Vinyasa method, which would in term influence Power Yoga and most modern Vinyasa practice.

- B.K.S. Iyengar, who would found the Iyengar method, which would systematize and refine the principles of physical alignment that are an important part of modern yoga practice.

- T.K.V. Desikachar, Krishnamacharya’s son, who would become highly influential in developing yoga as a highly personalized therapeutic practice appropriate for people with mobility issues and health challenges.

- Indra Devi, one of the earliest students from the west to travel to India to study Asana. She would become popular amongst the Hollywood elite and gain many celebrity pupils including Greta Garbo and Eva Gabor. She would also live to be 102 years old!

- Srivatsa Ramaswami, one of the only surviving long-term students of Krishnamacharya. He teaches a style of Vinyasa Yoga that is notably different from the Ashtanga Vinyasa method, which he calls Vinyasa Krama. It emphasizes a personalized approach in which a student can build a practice out of several modular sequences each of which contains poses of increasing difficulty.

Swami Sivananda

Another important guru who would help to popularize Hatha Yoga, not only in the west but in India as well, was Swami Sivananda. Sivananda was a physician who practiced in British Malaya, modern-day Malaysia, for 10 years before returning to India to become a monastic.

He traveled India extensively, learning from the masters of his time, like Ramana Maharshi and Sri Aurobindo, before settling in the holy city of Rishikesh.

Sivananda felt that medical science was only healing on a superficial level and began a campaign to promote Yoga as a tool for deeper physical healing, as well as healing of the mind and spirit. He founded the Divine Life Society in 1936, which produced spiritual literature that would be distributed free of charge.

Like Krishnamacharya, Sivananda would also influence several disciples who would go on to found large organizations dedicated to the education and promotion of Yoga. These include:

– Swami Vishnudevananda, who would found the first Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centre in Montreal, Canada in 1959. From there he would set up a Yoga camp in Val-Morin, Quebec, which would become the model for the modern yoga retreat centre, a place where ordinary people could take a spiritual vacation and return to their daily lives recharged and rejuvenated.

This centre would eventually become the headquarters of the Sivananda Yoga organization, which now has 28 centres and ashrams all over the world.

– Swami Satyananda, who would become enormously influential in India by founding the Bihar School Of Yoga, now one of the largest yoga centres in the world. The Bihar School of Yoga is most well known because of it’s publishing house, which has endeavored to preserve, translate and publish countless yogic texts, some of which may have otherwise fallen into obscurity.

Ram Dass and the 1960’s

The 1960s saw an explosion of interest in Indian culture and spiritual practices, including Yoga and Meditation.

Swami Satchidananda would give the opening address at Woodstock, the Beatles would travel to Rishikesh and study meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and a whole generation would be exposed to the work of musicians like Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha.

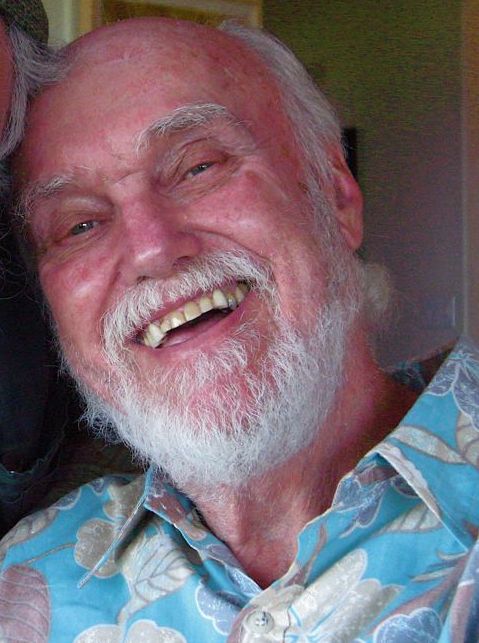

Richard Alpert was a professor of psychology at Harvard University, where he would gain notoriety for experimenting with psychedelic drugs like LSD and Psilocybin alongside the notorious Timothy Leary.

Alpert would eventually be fired from Harvard in a highly publicized scandal, and he and Leary would go on to become counter-cultural figures during the cultural upheaval of the 1960s. However, while Leary reveled in his controversial celebrity, Alpert would eventually become disillusioned and traveled to the East in search of answers.

While in India he met the spiritual teacher Neem Karoli Baba, who would become his guru, and was given the name Ram Dass. After studying in the foothills of the Himalayas for a short while he returned to America and published the book “Be Here Now”.

Be Here Now was one of the first books published that articulated the yogic spiritual path specifically to a western audience disillusioned with organized religion and without any previous experience with Indian culture. It became enormously influential with western spiritual seekers and has sold over 2 million copies.

Be Here Now started the wave of western students traveling to India to learn Yoga and to this day it can be found in the backpacks of traveling yogis from Rishikesh to Bali.

Yoga Today.

Today, Yoga is big business.

Tourists flock to retreat centres in India and abroad to improve their Sun Salutations.

Mindfulness, a form of meditation, is being heavily studied by western academics and put into practice at schools and hospitals.

The internet gives the opportunity for anyone to learn through popular sites like Yogaglo, Alomoves or Omstars.

Whether you love it or hate it, Yoga has gone from a secretive monastic practice to a mainstream cultural institution.

Would Vivekananda have guessed that the popularization of his beloved yoga would lead to a boom in the sales of colorful lycra pants and over-engineered rubber mats? We’ll never know.

It doesn’t really matter at the end of the day because, ultimately, Yoga is about what it was always about. When you sit on your cushion and clear away the unnecessary thoughts that clutter your mind, you are the same as the sage sitting on a straw mat three thousand years ago.

You have the same basic essence and it connects you with everything around you.

The history of Yoga is a complex and monumental topic. We’ve done our best to summarize it here.

However, the best way to learn about Yoga is to come to India and study it with a master. Our Multi-Style Retreats and Teacher Trainings are the perfect way to dive deep into this ancient practice.

You’ll learn the practice, as well as the history and philosophy of Yoga from teachers who have spent their whole lives immersed in the culture of Yoga.

Register today and become a part of Yoga’s future!

Check out our other post:

Responses